遥か昔45年前、私が大学生の頃、NHK教育テレビで中級英会話が放送されており、よく見ていました。講師は國弘正雄(くにひろ まさお)先生、アシスタント講師としてMarsha Krakower(マーシャ・ クラッカワー)さんで、確か海外の方とのトークショウのような進行だったと思います。

國弘正雄先生は英語の同時通訳の草分け的な存在で、1969年にアポロ11号の月面着陸を伝えるテレビ中継番組で同時通訳された方です。またマーシャ・クラッカワーさんはコロンビア大学大学院修了後、NHKテレビ・ラジオの 「英語会話」 の講師をされ、聖心女子大学で教鞭を取られた方です。

私は大学受験のための英語を勉強しただけであり、時事英語の表現や単語などむずかしさは常に感じていましたが、お二人の流暢な英語のお話しに魅了されました。國弘先生にはお目にかかったことはありませんが、マーシャ・クラッカワーさんには、当時時々ペリカンブックスやペンギンブックスなどの洋書を買 いに行っていた銀座のイエナ書店でお見かけしたような記憶があります。銀座のイエナ書店は、狭い階段を上っていくと洋書売り場となっていました。銀座のイエナ書店、日本橋の丸善、渋谷の大盛堂の最上階のフロアなど洋書売り場へは学生の時に時々行っていました。

さて、NHK英語会話中級で聞いた言葉、今でも「公民権運動」という言葉が記憶に残っています。この講座を聞いていたのが1975年頃だったので、キング牧師の公民権運動がテレビ報道でも取り上げられ、その活動を行っている方と國弘先生やクラッカワーさんが英語で議論しており、そのときに聞いた「公民権運動」という言葉が記憶に残っていて、私たち日本人が成人になれば皆持っている、例えば選挙権がアメリカの黒人はこの選挙権を獲得するために長く苦しい運動を続けていかなければならなかったなどを知りショッキングを受け、それ以来ずっとこの「公民権運動」ということが気になってました。

日本では、明治22年(1889年)に大日本帝国憲法が発布され「満25歳以上、直接国税15円(現在の60万円~70万円)以上を納める男子」に選挙権が与えられ、全人口の1%でした。大正14年(1925年)には25才以上のすべての男性が選挙権を持ち、そして戦後、昭和20年(1945年)に女性の参政権が認められ、満20歳以上のすべての国民が選挙権を持つようになりました。

Wikipediaによると、公民権運動とは、1950年代から1960年代にかけて、アメリカの黒人(アフリカ系アメリカ人)が、公民権の適用と人種差別の解消を求めて行った運動であり、公職に関する選挙権・被選挙権を通じて政治に参加する地位・資格、公務員として任用される権利(公務就任権)などの総称で、参政権、市民権とほぼ同じ意味です。

ここで、「アメリカの小学生が学ぶ歴史教科書」から公民権運動を抜粋してその公民権運動について学んでみたいと思います。

ジム·クロウ法

1950年代は多くのアメリカ人にとって良き時代でしたが、アフリカ系アメリカ人は社会全体的な繁栄を享受できませんでした。アメリカの歴史が始まって以来、たいていの黒人は南部の州に住んでいました。そこの大農園で働く奴隷として連れて来られたのでした。 1900年には、アフリカ系アメリカ人の10人に9人が南部で暮らしていました。そして、黒人は新しいチャンスを見出そうと、第1次世界大戦の頃に北部に移り始めました。第2次大戦の戦中と戦後には、北へ向かう移住の流れは大洪水となりました。1950年には、およそ3分の1のアフリカ系アメリカ人が南部以外のところで生活していたのです。しかし、北部にやって来た多くの人が、まだ対等に扱われていないことに気づき失望しました。もし、1950年代に北部の都市郊外住宅地を車で通り抜けても、黒人の姿はあまり見られなかったでしょう。

しかし、最も抑圧されていたのは南部に残った黒人たちでした。南部では、ほとんどの黒人にアメリカ国民の基本的な権利が与えられていませんでした。選挙権です。南部の白人は多くの術策を使ってアフリカ系アメリカ人に投票させませんでした。黒人は投票するために「人頭税」を支払わなければならないと言われることがありましたが、たいていの黒人は貧しく、払うことができませんでした。また白人の有権者が受ける必要のない、複雑な試験を受けさせられることもありました。そしてまた、投票しようとすると暴力で脅されるということもあったのです。

さらに、南部の黒人は厳格な人種差別(隔離)制度で抑圧されていました。黒人は白人と交わることを許されませんでした。黒人居住区に住み、黒人だけの学校に行かなければならなかったのです。

事実、南部の州は人種を引き離すための何百もの法律を作りました。これらは総じて「ジム·クロウ」法(Jim Crow Law)と呼ばれていました(「ジム·クロウ」とは黒人に対する侮辱的な俗語です)。あるジム·クロウ法は、バスや電車のなかで白人と黒人は分離されていなければならないと明記していました。また、病院は白人と黒人用に別々の区城を設けなければならないと定めたり、白人と黒人は同じチームでスポーツしてはいけないと定めた法律もありました。同じ水飲み場やトイレを使うことすら許されませんでした。

南部のいたる所で、公衆便所に「白人専用」とか「黒人用」と書かれた標示がありました。ジム·クロウ法の中には馬鹿げたものもありました。アラバマ州のある法律は黒人が白人とチェッカーをすることを禁じていたのです。

しかし、そんな法律は笑いごとではありませんでした。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の機会を厳しく制限していました。 さらに、白人と付き合うには著しく「劣って」いるとして、黒人を侮辱していたのです。

この法律は、南アフリカのアパルトヘイトにも匹敵する非道で不公平な制度を生み出していたのです。 1950年代にアフリカ系アメリカ人のジム·クロウ法に対する怒りは、アメリカにおける人種差別をなくそうとする大きな運動に発展しました。これが公民権運動です。

ローザ·パークスとモンゴメリーでのバス乗車拒否

1955年12月のある日、 ローザ·パークスというアフリカ系アメリカ人の女性がアラバマ州モンゴメリーでバスに乗りました。 モンゴメリーのすべてのバスは、白人は前に、黒人は後ろに座るようになっていました。パークスは「白人専用」席のすぐ後ろの列に腰掛けました。パスはすでに混みあっていました。2つ先の停留所で、数人の白人がそのバスに乗り込んできました。そのうちの1人は白人専用席で空席を見つけられなかったのです。

そこで、バスの運転手は 「黒人用」の最前列に座っていた4人に声をかけ、白人を座らせるために、その列から離れるよう命じました。黒人乗客のうち3人は従いました。しかし、 4人目のローザ·パークスは席についたままでした。パークスは1日の長時間労働で疲れいたし、白人が座るためになぜ自分が立たなければならないのか理解できなかったのです。 運転手は警察を呼び、パークスは逮捕されました。パスの中で白人と黒人を分離しなければならないことを記したジム·クロウ法に違反したというのです。モンゴメリー中のアフリカ系アメリカ人はパークスの勇気を称賛し、彼女の逮捕に怒りました。 そして、市バスの乗車を拒否することで、抗議しようと決めました。 アフリカ系アメリカ人は黒人と白人の乗客が平等に扱われるまで、バスへの乗車を拒否したのです。モンゴメリーではバスの乗客の多くが黒人だったので、このボイコットによってバス会社は多額の損失を出しました。

それでもなお、バス会社はジム·クロウ規則の廃止を拒みました。それで、アフリカ系アメリカ人は乗車拒否を1年以上も続けました。バスで通勤する代わりに、黒人たちは歩いたり、黒人のタクシーを使ったのです。ボイコットは苦痛でしたが、モンゴメリーのアフリカ系アメリカ人は権利のために戦おうと堅く決意していたのです。乗車拒否が始まってから1年少々が過ぎた1956年12月に、米最高裁判所が決断を下しました。裁判所によれば、バスで人種差別するモンゴメリーのやり方は憲法に違反しているというのです。 市バスでは差別がなくなり、ボイコットは終わりました。アメ

リカ中の人は、モンゴメリーのアフリカ系アメリカ人の決意に心を打たれました。特に、このボイコットを率いた若い黒人牧師、マーティンルーサー·キング博士に感銘を受けました。

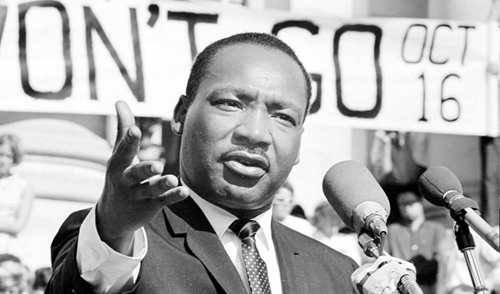

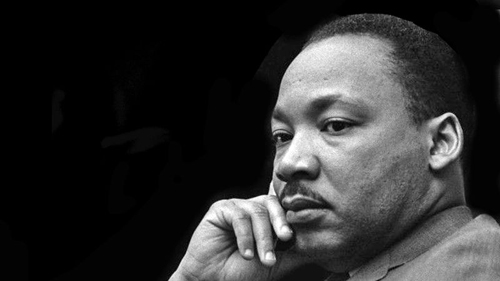

マーティン·ルーサー·キング

バスの乗車拒否を指揮したとき、マーティン·ルーサーキングは弱冠26歳でした。 キングはジョージア州アトランタで生まれ、彼の父親は牧師でした。キング自身もモアハウス大学在学中に牧師となります。後にボストン大学に進み博士号を取得しました。

いくつかの理由で、キングは最も重要な公民権運動の指導者と考えられています。 彼は教養が高く、雄弁家でした。 また、勇敢でめり、その運動のために収監や死の危険を冒すことすら厭わなかったのです。しかし、何にもまして、彼の高い道徳的な理想に数多くの信奉者が惹きつけられたのでしょう。キングは、キリスト教徒として、すべての者を、自分を迫害する者すらも愛するべきであるというイエスの教えに従ったのです。 モンゴメリーで彼は支持者たちに言いました。

毎日逮捕されても、毎日搾取されても、毎日踏みつぶされてもても、けっしてその人たちを憎むようになってはなりません。我々は愛という武器を使わなくてはならないのです。

キングの導いた運動は非暴力を貫きました。キングは、アフリカ系アメリカ人は武器を取るべきでない、「消極的抵抗」で不公平な制度と戦うべきだと述べました。消極的抵抗とは物静かに、しかし毅然と不当な法律に従うことを拒むことです。 ローザ·パークスはバスで席から立ち上がらなかった時、消極的抵抗を実践しました。キングは、もしたくさんの人が消極的抵抗を行えば、不公平な法律は変わらざるをえないと考えていました。

消極的抵抗の1つの有効的な形態は「座り込み」です。 1960年初頭に、4人の黒人の大学生がノースカロライナ州グリーンズボロの軽食堂で座り込みを行いました。そこは白人客にのみ食事を出していたので、誰も彼らの接客をしませんでした。その黒人の学生たちは白人客に愚弄されましたが、閉店まで座り続けました。その次の日にはより多くの学生の一団が「座り込み」のために現れ、そのまた次の日にはさらに多くの学生がやって来ました。

他の人たちもその学生たちのデモを聞きつけました。南部のいたるところで、アフリカ系アメリカ人は黒人の接客を拒むレストランや商店で「座り込み」を始めました。座り込みにより、ジム·クロウ法の不当性をアピールしたのです。 マーティンルーサー·キングはこの方策を奨励しました。1960年10月、キング自身もアトランタのデパートの座り込みに参加したことで逮捕されています。

キング、バーミンガムへ

1963年にキングはアラバマ州バーミンガムという大都市で、人種差別をなくすキャンペーンを行いました。キングはバーミンガムをアメリカで最も人種差別の激しい都市とみなしていました。バーミンガム警察はアフリカ系アメリカ人への残酷な虐待で悪名高かったのです。キングはバーミンガムに来て、ボイコット、座り込み、デモ行進を指揮しました。あるとき彼は逮捕され、1週間刑務所に人れられてしまいます。 しかし、何事もキングや彼の信奉者を止めることはできませんでした。デモが何週にもわたって続くにつれ、バーミンガム警察はますます残忍になっていきました。 デモ行進を解散させるために消防ホースや警察犬を使い始めたのです。うなる警察犬は黒人男性、女性、子供を追い回します。消防ホースは強力な水の噴射で、行進する人たちを地面に叩きつけました。人種差別主義者の白人がバーミンガムの黒人を残酷に虐待する写真は、全米中で新聞に印刷され、テレビで放映されました。多くのアメリカ人は目にした光景に激しく憤り、白人の残虐さを非難し、平等の権利を求めるアフリカ系アメリカ人に共感し始めました。6週間もたたないうちに、バーミンガム市はほとんどの人種差別を廃止することに合意します。キングとその信奉者は勝ったのです。その勝利はバーミンガムを超えて拡大しました。人種を問わず数多くのアメリカ人が、大胆な新しい法律、人種差別を永久に無くす法律を作るべきであると確信したのです。

ワシントン行進

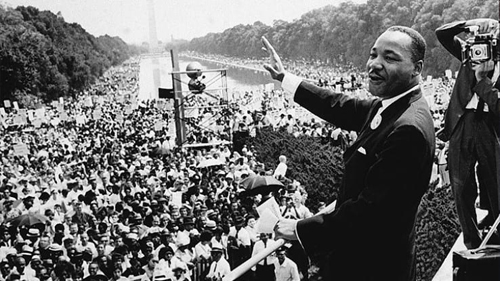

1963年の夏、議会は公民権法という抜本的な新しい法律を通過させるかどうかを議論していました。労働組合のリーダーだったフィリップ·ランドルフは新しい法律に賛同を示すために、 壮大な「ワシントン行進」を計画しました。

1963年8月28日、ワシントンで行進が催されました。これほど大きなデモが首都で行われたことはありませんでした。 20万人以上の人が参加し、約4分の1は白人でした。デモ参加者は、人種差別の廃絶を求めるプラカードを掲げました。 行進しながら、公民権運動の歌であった霊歌「勝利を我等に」を歌いました。

勝利は我らの手に

勝利は我らの手に

勝利は我らの手に

いつの日か

こころの奥底で

私は信じる

勝利は我らの手に

いつの日か

行進の最後に、デモ参加者はリンカーン記念碑のところに集結しました。陽がふりそそぐ熱い日でした。巨大な群衆の雰囲気は希望にあふれ、楽しげですらありました。多数の 公民権運動のリーダーが演説を行いました。そして、マーティン・ルーサー・キングが立ち上がり、海のようにも見える無数の顔に話し掛けました。トマス・ジェファソンの言葉を引用しながら、牧師の太い声で、情熱的な言葉を述べました。

公民権運動のリーダーが演説を行いました。そして、マーティン・ルーサー・キングが立ち上がり、海のようにも見える無数の顔に話し掛けました。トマス・ジェファソンの言葉を引用しながら、牧師の太い声で、情熱的な言葉を述べました。

友よ、我々は今日も明日も困難に直面するに違いないが、

それでも私には夢があります。

その夢とは、 いつの日かこの国が立ち上がり、

その信念の真の意味を実現することです。一

我々は次の真理を自明のことと考える。

人間はみな 平等に創られたのだ。

私には夢があります。いつの日か私の幼い4人の子供たちが、

肌の色ではなく人格の良し悪しで判断される国に住めるように

なるという夢です。

今、 私には夢があるのです。

So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the dif-

ficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

It is a dreamdeeply rooted in the American dream that one day this nation will

rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed-we hold thesetruths

to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. . ..

I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation

where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the

content of their character.

I have a dream today!

キングが話すのを聞いた人々も、テレビでそれを見ていた何百万という人たちも、彼のメッセージが持つ力に圧倒されました。今日、キングが「私には夢がある」と語った演説の言葉はアメリカではく知られたものとなっています。

ジョンソンと公民権

ジョンソンが初めて大統領になったとき、一部のアフリカ系アメリカ人は大統領を信頼していいかどうか分かりませんでした。なんといっても、彼は1世紀ぶりの南部出身の大統領であり、南部のアフリカ系アメリカ人は依然として権利のためにとくに一所懸命に戦っていたのです。 しかし、ジョンソンはテキサスで育った時に目の当たりにした人種差別を憎んでいて、 公民権を強力に支持しました。

ジョンソンの大統領任期中に、 公民権に関する2つのもっとも重要な法律が制定されました。1964年公民権法は、人種、宗教、もしくは一族の出身国でいかなる人をも差別することを違法としました。公民権法の制定後、雇用主は採用の際に人を差別することができなくなりました。労働組合は組合員を受け入れる時に差別することはできません。ホテルやレストランといった職業では、支払い能力のあるすべての人に仕えなければなりませんでした。

1965年投票権法の通過で、アメリカは平等な権利にさらに1歩近づきます。この法律では、すべての国民が選挙権を有するとし、大部分の南部の黒人から投票権を奪うために使われてきた数多くの策略が使えなくなりました。もし、ある州が誰かが選挙登録するのを拒めば、連邦政府がその人を登録することができるようになりました。いまや、アメリカ中のアフリカ系アメリカ人が投票による力を得たのです。その後の数年間で、ますます多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人が選挙により公職につきました。1965年にはアメリカの都市に黒人の市長はいませんでしたが、1979年には、アト

ランタ、デトロイト、ロサンゼルス等の大都市を含む数十の都市でアフリカ系アメリカ人の市長が誕生していました。

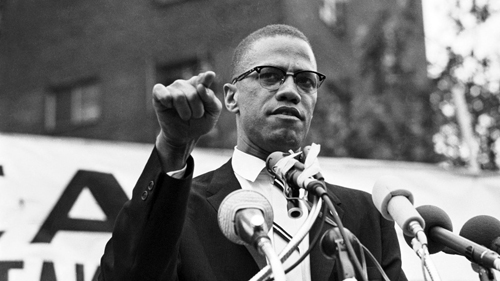

公民権運動のリーダーの死

1960年半ばに公民権運動は分裂していきます。 マルコムXのように、一部の若い黒人たちは差別撤発への歩みが遅すぎると考えていました。マーティン·ルーサー·キングの消極的抵抗の戦略に疑問を投げかけ始めたのです。 彼らはブラック·ムスリムのように人種差別撤廃の目標すら疑問視しました。ますます多くの若い黒人が差別撤廃のゴールを拒絶し、 「黒人至上主義」について語るようになりました。

「黒人至上主義」は人によって意味が変わってきます。 ある人には、黒人が自分たちの社会の完全な支配権を握ることを意味します。 またある人にとっては、白人に対する暴力的な革命で武器を取ることを意味するのです。 マーティン·ルーサーキングは黒人至上主義の話に当惑しました。そして、 アフリカ系アメリカ人に対し、 平和的な手段を行使し、非人種差別的な白人と手を組むよう呼びかけました。

キングは運動をどんどん進め、国中で平和的な抗議活動を指導しました。彼は自分が危険にさらされていることを知っていました。

キングとその信奉者は非暴力的でしたが、公民権の考え方に反対する暴力的な人々に直面しました。 1960年代初頭に、何人かの公民権運動家が殺害されています。 何年もの間、 キングも殺されるかもしれないと感じていました。 ケネディ大統領が殺された日、キングは妻に向かって「これが私に起ころうとしていることだ」と言ってます。

1968年4月、キングは黒人労働者の同一賃金を求めるデモを率いるためにテネシー州メンフィスに 行きました。 そして、自分がたいして長く生きていられないかもしれないことを承知していると聴衆に告げました。そして、聖書に出てくる古代のユダヤ人のリーダーであるモーゼの話に触れました。神から約束された地への長い旅のあいだ、モーゼは人々を導いたのでした。しかし、 その約束の土地に着く寸前で、モーゼは死にます。死ぬ前に山の頂からその土地を

行きました。 そして、自分がたいして長く生きていられないかもしれないことを承知していると聴衆に告げました。そして、聖書に出てくる古代のユダヤ人のリーダーであるモーゼの話に触れました。神から約束された地への長い旅のあいだ、モーゼは人々を導いたのでした。しかし、 その約束の土地に着く寸前で、モーゼは死にます。死ぬ前に山の頂からその土地を

一瞥したのでした。キングはスピーチの中で次のように話しました。

すべての人と同様、私も長生きしたいと思う。

しかし、今そのことを気に掛けてはいない。

私はただ神の意思にこたえたいだけだ。

神は私が山に登るのを許し、私はあたりを見渡し、

約束の地を見た。

あなたたちと一緒にそこには行けないかもしれない。

しかし、今晩みんなに分かってもらいたい。

我々は約束の地に行くのだと。

私は今晩とても幸せだ。

心配することは何もない。

恐れる者は誰もいない。

次の日、キングは夕食に向かうためにモーテルの部屋を出たとき、暗殺者に射殺されました。 今や、 差別のない「約束の地」へ人々を導くのは他のリーダーに任せられました。

マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアの誕生日は1月15日であり、月曜休日統一法により、1月の第三月曜日はマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアの日(Martin Luther King Jr. Day) としてアメリカ合衆国の国民の祝日となっています。

1968年4月4日に遊説活動中のテネシー州メンフィスにあるメイソン・テンプルで “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”(私は山頂に達した)と遊説しました。その後、メンフィス市内にあるロレイン・モーテル306号室前のバルコニーで、その夜の集会での演奏音楽の曲目を打ち合わせ中に、白人男性のジェームズ・アール・レイに撃たれ、病院に搬送されましたが亡くなりました。

ジョージア州アトランタのThe Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Siteにある彼の墓標には「Free at last. Free at last, Thank God Almighty I’m Free at last.」(ついに自由を得た)と記されています。

Martin Luther King Jr. “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”

Memphis, Tennessee – April 3, 1968

Thank you very kindly, my friends. As I listened to Ralph Abernathy in his eloquent and generous introduction and then thought about myself, I wondered who he was talking about. [laughter] It’s always good to have your closest friend and associate say something good about you. And Ralph is the best friend that I have in the world. I’m delighted to see each of you here tonight in spite of a storm warning. You reveal that you are determined to go on anyhow.

Something is happening in Memphis; something is happening in our world. And you know, if I were standing at the beginning of time, with the possibility of taking a kind of general and panoramic view of the whole human history up to now, and the Almighty said to me, “Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?” – I would take my mental flight by Egypt and I would watch God’s children in their magnificent trek from the dark dungeons of Egypt through, or rather across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land. And in spite of its magnificence, I wouldn’t stop there. I would move on by Greece, and take my mind to Mount Olympus. And I would see Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Euripides and Aristophanes assembled around the Parthenon. And I would watch them around the Parthenon as they discussed the great and eternal issues of reality. But I wouldn’t stop there.

I would go on, even to the great heyday of the Roman Empire. And I would see developments around there, through various emperors and leaders. But I wouldn’t stop there. I would even come up to the day of the Renaissance, and get a quick picture of all that the Renaissance did for the cultural and aesthetic life of man. But I wouldn’t stop there. I would even go by the way that the man for whom I’m named had his habitat. And I would watch Martin Luther as he tacked his ninety-five theses on the door at the church of Wittenberg.

But I wouldn’t stop there. I would come on up even to 1863, and watch a vacillating president by the name of Abraham Lincoln finally come to the conclusion that he had to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. But I wouldn’t stop there.

[applause]

I would even come up to the early thirties, and see a man grappling with the problems of the bankruptcy of his nation. And come with an eloquent cry that we have nothing to fear but fear itself.

But I wouldn’t stop there. Strangely enough, I would turn to the Almighty, and say, “If you allow me to live just a few years in the second half of the 20th century, I will be happy.” [applause] Now that’s a strange statement to make, because the world is all messed up. The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land; confusion all around. That’s a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars. And I see God working in this period of the twentieth century in a way that men, in some strange way, are responding – something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee – the cry is always the same – “We want to be free.”

And another reason that I’m happy to live in this period is that we have been forced to a point where we’re going to have to grapple with the problems that men have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demand didn’t force them to do it. Survival demands that we grapple with them. Men, for years now, have been talking about war and peace. But now, no longer can they just talk about it. It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it’s nonviolence or nonexistence! [applause] That is where we are today.

And also in the human rights revolution, if something isn’t done, and done in a hurry, to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is doomed. Now, I’m just happy that God has allowed me to live in this period, to see what is unfolding. And I’m happy that He’s allowed me to be in Memphis.

I can remember, I can remember when Negroes were just going around as Ralph has said, so often, scratching where they didn’t itch, and laughing when they were not tickled. But that day is all over. We mean business now, and we are determined to gain our rightful place in God’s world.

And that’s all this whole thing is about. We aren’t engaged in any negative protest and in any negative arguments with anybody. We are saying that we are determined to be men. We are determined to be people. We are saying that we are God’s children. And that we don’t have to live like we are forced to live.

Now, what does all of this mean in this great period of history? It means that we’ve got to stay together. We’ve got to stay together and maintain unity. You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.

Secondly, let us keep the issues where they are. The issue is injustice. The issue is the refusal of Memphis to be fair and honest in its dealings with its public servants who happen to be sanitation workers. Now, we’ve got to keep attention on that. That’s always the problem with a little violence. You know what happened the other day, and the press dealt only with the window-breaking. I read the articles. They very seldom got around to mentioning the fact that one thousand, three hundred sanitation workers were on strike, and that Memphis is not being fair to them, and that Mayor Loeb is in dire need of a doctor. They didn’t get around to that.

[applause]

Now we’re going to march again, and we’ve got to march again, in order to put the issue where it is supposed to be – and force everybody to see that there are thirteen hundred of God’s children here suffering, sometimes going hungry, going through dark and dreary nights wondering how this thing is going to come out. That’s the issue. And we’ve got to say to the nation: we know how it’s coming out. For when people get caught up with that which is right and they are willing to sacrifice for it, there is no stopping point short of victory!

[applause]

We aren’t going to let any mace stop us. We are masters in our nonviolent movement in disarming police forces; they don’t know what to do, I’ve seen them so often. I remember in Birmingham, Alabama, when we were in that majestic struggle there, we would move out of the 16th Street Baptist Church day after day; by the hundreds we would move out. And Bull Connor would tell them to send the dogs forth, and they did come; but we just went before the dogs singing, “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around.” Bull Connor next would say, “Turn the fire hoses on.” And as I said to you the other night, Bull Connor didn’t know history. He knew a kind of physics that somehow didn’t relate to the transphysics that we knew about. And that was the fact that there was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out. And we went before the fire hoses; we had known water. If we were Baptist or some other denomination, we had been immersed. If we were Methodist, and some others, we had been sprinkled, but we knew water. That couldn’t stop us.

And we just went on before the dogs and we would look at them; and we’d go on before the water hoses and we would look at it, and we’d just go on singing, “Over my head I see freedom in the air.” And then we would be thrown in the paddy wagons, and sometimes we were stacked in there like sardines in a can. And they would throw us in, and old Bull would say, “Take them off,” and they did; and we would just go on in the paddy wagon singing, “We Shall Overcome.” And every now and then we’d get in the jail, and we’d see the jailers looking through the windows being moved by our prayers, and being moved by our words and our songs. And there was a power there which Bull Connor couldn’t adjust to; and so we ended up transforming Bull into a steer, and we won our struggle in Birmingham.

[applause]

Now we’ve got to go on in Memphis just like that. I call upon you to be with us when we go out Monday. Now about injunctions: We have an injunction and we’re going into court tomorrow morning to fight this illegal, unconstitutional injunction. All we say to America is, “Be true to what you said on paper.” [applause] If I lived in China or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges, because they hadn’t committed themselves to that over there. But somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say we aren’t going to let any dogs or water hoses turn us around, we aren’t going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.

We need all of you. And you know what’s beautiful to me, is to see all of these ministers of the Gospel. It’s a marvelous picture. Who is it that is supposed to articulate the longings and aspirations of the people more than the preacher? Somehow the preacher must have a kind of fire shut up in his bones and whenever injustice is around, he must tell it. Somehow the preacher must be an Amos, and say, “When God speaks, who can but prophesy?” Again, with Amos, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Somehow, the preacher must say with Jesus, “The spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to deal with the problems of the poor.”

And I want to commend the preachers, under the leadership of these noble men: James Lawson, one who has been in this struggle for many years; he’s been to jail for struggling; he’s been kicked out of Vanderbilt University for this struggle, but he’s still going on, fighting for the rights of his people. [applause] Rev. Ralph Jackson, Billy Kiles; I could just go right on down the list, but time will not permit. But I want to thank all of them. And I want you to thank them, because so often, preachers aren’t concerned about anything but themselves. And I’m always happy to see a relevant ministry.

It’s all right to talk about “long white robes over yonder,” in all of its symbolism. But ultimately people want some suits and dresses and shoes to wear down here! It’s all right to talk about “streets flowing with milk and honey,” but God has commanded us to be concerned about the slums down here, and his children who can’t eat three square meals a day. It’s all right to talk about the new Jerusalem, but one day, God’s preachers must talk about the new New York, the new Atlanta, the new Philadelphia, the new Los Angeles, the new Memphis, Tennessee. [applause] This is what we have to do.

Now the other thing we’ll have to do is this: Always anchor our external direct action with the power of economic withdrawal. Now, we are poor people. Individually, we are poor when you compare us with white society in America. We are poor. Never stop and forget that collectively – that means all of us together – collectively we are richer than all the nations in the world, with the exception of nine. Did you ever think about that? After you leave the United States, Soviet Russia, Great Britain, West Germany, France, and I could name the others, the American Negro collectively is richer than most nations of the world. We have an annual income of more than thirty billion dollars a year, which is more than all of the exports of the United States, and more than the national budget of Canada. Did you know that? That’s power right there, if we know how to pool it.

[applause]

We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles. We don’t need any Molotov cocktails. We just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, “God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you.”

And so, as a result of this, we are asking you tonight, to go out and tell your neighbors not to buy Coca-Cola in Memphis. Go by and tell them not to buy Sealtest milk. Tell them not to buy – what is the other bread? – Wonder Bread. And what is the other bread company, Jesse? Tell them not to buy Hart’s bread. As Jesse Jackson has said, up to now, only the garbage men have been feeling pain; now we must kind of redistribute the pain. [applause] We are choosing these companies because they haven’t been fair in their hiring policies; and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.

But not only that, we’ve got to strengthen black institutions. I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank-we want a “bank-in” movement in Memphis. So go by the savings and loan association. I’m not asking you something we don’t do ourselves at SCLC. Judge Hooks and others will tell you that we have an account here in the savings and loan association from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. We’re telling you to follow what we’re doing. Put your money there. You have six or seven black insurance companies in the city of Memphis. Take out your insurance there. We want to have an “insurance-in.”

Now these are some practical things we can do. We begin the process of building a greater economic base. And at the same time, we are putting pressure where it really hurts. I ask you to follow through here.

Now, let me say as I move to my conclusion that we’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point, in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through. [applause] And when we have our march, you need to be there. If it means leaving work, if it means leaving school, be there. [applause] Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.

[applause]

Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness. One day a man came to Jesus; and he wanted to raise some questions about some vital matters in life. At points, he wanted to trick Jesus, and show him that he knew a little more than Jesus knew, and throw him off base. Now that question could have easily ended up in a philosophical and theological debate. But Jesus immediately pulled that question from mid-air, and placed it on a dangerous curve between Jerusalem and Jericho. And he talked about a certain man, who fell among thieves. You remember that a Levite and a priest passed by on the other side. They didn’t stop to help him. And finally a man of another race came by. He got down from his beast, decided not to be compassionate by proxy. But he got down with him, administering first aid, and helped the man in need. Jesus ended up saying, this was the good man, this was the great man, because he had the capacity to project the “I” into the “thou,” and to be concerned about his brother. Now you know, we use our imagination a great deal to try to determine why the priest and the Levite didn’t stop. At times we say they were busy going to a church meeting – an ecclesiastical gathering – and they had to get on down to Jerusalem so they wouldn’t be late for their meeting. At other times we would speculate that there was a religious law that “One who was engaged in religious ceremonials was not to touch a human body twenty-four hours before the ceremony.” And every now and then we begin to wonder whether maybe they were not going down to Jerusalem, or down to Jericho, rather to organize a “Jericho Road Improvement Association.” That’s a possibility. Maybe they felt that it was better to deal with the problem from the causal root, rather than to get bogged down with an individual effort.

But I’m going to tell you what my imagination tells me. It’s possible that those men were afraid. You see, the Jericho road is a dangerous road. I remember when Mrs. King and I were first in Jerusalem. We rented a car and drove from Jerusalem down to Jericho. And as soon as we got on that road, I said to my wife, “I can see why Jesus used this as the setting for his parable.” It’s a winding, meandering road. It’s really conducive for ambushing. You start out in Jerusalem, which is about 1,200 miles, or rather 1,200 feet, above sea level.

And by the time you get down to Jericho, fifteen or twenty minutes later, you’re about 2,200 feet below sea level. That’s a dangerous road. In the days of Jesus it came to be known as the “Bloody Pass.” And you know, it’s possible that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around. Or it’s possible that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking. And he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt, in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure. And so the first question that the Levite asked was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

That’s the question before you tonight. Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to my job?” Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?” The question is not, “If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?” The question is, “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?” That’s the question.

[applause]

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation. And I want to thank God, once more, for allowing me to be here with you.

You know, several years ago, I was in New York City autographing the first book that I had written. And while sitting there autographing books, a demented black woman came up. The only question I heard from her was, “Are you Martin Luther King?” And I was looking down writing, and I said yes. And the next minute I felt something beating on my chest. Before I knew it I had been stabbed by this demented woman. I was rushed to Harlem Hospital. It was a dark Saturday afternoon. And that blade had gone through, and the X-rays revealed that the tip of the blade was on the edge of my aorta, the main artery. And once that’s punctured, you drown in your own blood – that’s the end of you.

It came out in the New York Times the next morning, that if I had merely sneezed, I would have died. Well, about four days later, they allowed me, after the operation, after my chest had been opened, and the blade had been taken out, to move around in the wheelchair in the hospital. They allowed me to read some of the mail that came in, and from all over the states, and the world, kind letters came in. I read a few, but one of them I will never forget. I had received one from the President and the Vice President. I’ve forgotten what those telegrams said. I’d received a visit and a letter from the Governor of New York, but I’ve forgotten what the letter said. But there was another letter that came from a little girl, a young girl who was a student at the White Plains High School. And I looked at that letter, and I’ll never forget it. It said simply, “Dear Dr. King: I am a ninth-grade student at the White Plains High School.” She said, “While it should not matter, I would like to mention that I am a white girl. I read in the paper of your misfortune, and of your suffering. And I read that if you had sneezed, you would have died. And I’m simply writing you to say that I’m so happy that you didn’t sneeze.”

[applause]

And I want to say tonight, I want to say that I too am happy that I didn’t sneeze. Because if I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1960, when students all over the South started sitting-in at lunch counters. And I knew that as they were sitting in, they were really standing up for the best in the American dream. And taking the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1961 when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation in interstate travel. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1962, when Negroes in Albany, Georgia, decided to straighten their backs up. And whenever men and women straighten their backs up, they are going somewhere, because a man can’t ride your back unless it is bent! [applause] If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been here in 1963, when the black people of Birmingham, Alabama, aroused the conscience of this nation, and brought into being the Civil Rights Bill. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream that I had had. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been down in Selma, Alabama, to see the great movement there. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been in Memphis to see the community rally around those brothers and sisters who are suffering. I’m so happy that I didn’t sneeze.

[applause]

And they were telling me, now it doesn’t matter now. It really doesn’t matter what happens now. I left Atlanta this morning, and as we got started on the plane, there were six of us, the pilot said over the public address system, “We are sorry for the delay, but we have Dr. Martin Luther King on the plane. And to be sure that all of the bags were checked, and to be sure that nothing would be wrong on the plane, we had to check out everything carefully. And we’ve had the plane protected and guarded all night.”

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers?

Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. [applause] And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! So I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

[applause]

マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニア「私には夢がある」(演説全文)

(アメリカ国務省 アメリカンセンタージャパンより引用)

1963年8月28日

今日私は、米国史の中で、自由を求める最も偉大なデモとして歴史に残ることになるこの集会に、皆さんと共に参加できることを嬉しく思う。

100年前、ある偉大な米国民が、奴隷解放宣言に署名した。今われわれは、その人を象徴する坐像の前に立っている。この極めて重大な布告は、容赦の ない不正義の炎に焼かれていた何百万もの黒人奴隷たちに、大きな希望の光明として訪れた。それは、捕らわれの身にあった彼らの長い夜に終止符を打つ、喜び に満ちた夜明けとして訪れたのだった。

しかし100年を経た今日、黒人は依然として自由ではない。

100年を経た今日、黒人の生活は、悲しいことに依然として人種隔離の手かせと人種差別 の鎖によって縛られている。100年を経た今日、黒人は物質的繁栄という広大な海の真っ只中に浮かぶ、貧困という孤島に住んでいる。

100年を経た今日、 黒人は依然として米国社会の片隅で惨めな暮らしを送り、自国にいながら、まるで亡命者のような生活を送っている。

そこで私たちは今日、この恥ずべき状況を 劇的に訴えるために、ここに集まったのである。

ある意味で、われわれは、小切手を換金するためにわが国の首都に来ている。われわれの共和国の建築家たちが合衆国憲法と独立宣言に崇高な言葉を書き記した 時、彼らは、あらゆる米国民が継承することになる約束手形に署名したのである。この手形は、すべての人々は、白人と同じく黒人も、生命、自由、そして幸福 の追求という不可侵の権利を保証される、という約束だった。

今日米国が、黒人の市民に関する限り、この約束手形を不渡りにしていることは明らかである。米国はこの神聖な義務を果たす代わりに、黒人に対して不良小切手を渡した。その小切手は「残高不足」の印をつけられて戻ってきた。

だがわれわれは、正義の銀行が破産しているなどと思いたくない。この国の可能性を納めた大きな金庫が資金不足であるなどと信じたくない。だからわれ われは、この小切手を換金するために来ているのである。自由という財産と正義という保障を、請求に応じて受け取ることができるこの小切手を換金するため に、ここにやって来たのだ。われわれはまた、現在の極めて緊迫している事態を米国に思い出させるために、この神聖な場所に来ている。今は、冷却期間を置く という贅沢にふけったり、漸進主義という鎮静薬を飲んだりしている時ではない。今こそ、民主主義の約束を現実にする時である。今こそ、暗くて荒廃した人種 差別の谷から立ち上がり、日の当たる人種的正義の道へと歩む時である。今こそ、われわれの国を、人種的不正の流砂から、兄弟愛の揺るぎない岩盤の上へと引 き上げる時である。今こそ、すべての神の子たちにとって、正義を現実とする時である。

この緊急事態を見過ごせば、この国にとって致命的となるであろう。黒人たちの正当な不満に満ちたこの酷暑の夏は、自由と平等の爽快な秋が到来しない 限り、終わることがない。1963年は、終わりではなく始まりである。黒人はたまっていた鬱憤を晴らす必要があっただけだから、もうこれで満足するだろう と期待する人々は、米国が元の状態に戻ったならば、たたき起こされることになるだろう。黒人に公民権が与えられるまでは、米国には安息も平穏が訪れること はない。正義の明るい日が出現するまで、反乱の旋風はこの国の土台を揺るがし続けるだろう。

しかし私には、正義の殿堂の温かな入り口に立つ同胞たちに対して言わなければならないことがある。正当な居場所を確保する過程で、われわれは不正な 行為を犯してはならない。われわれは、敵意と憎悪の杯を干すことによって、自由への渇きをいやそうとしないようにしよう。われわれは、絶えず尊厳と規律の 高い次元での闘争を展開していかなければならない。われわれの創造的な抗議を、肉体的暴力へ堕落させてはならない。われわれは、肉体的な力に魂の力で対抗 するという荘厳な高みに、何度も繰り返し上がらなければならない。信じがたい新たな闘志が黒人社会全体を包み込んでいるが、それがすべての白人に対する不 信につながることがあってはならない。なぜなら、われわれの白人の兄弟の多くは、今日彼らがここにいることからも証明されるように、彼らの運命がわれわれ の運命と結び付いていることを認識するようになったからである。また、彼らの自由がわれわれの自由と分かち難く結びついていることを認識するようになった からである。われわれは、たった一人で歩くことはできない。

そして、歩くからには、前進あるのみということを心に誓わなければならない。引き返すことはできないのである。公民権運動に献身する人々に対して、 「あなたはいつになったら満足するのか」と聞く人たちもいる。われわれは、黒人が警察の言語に絶する恐ろしい残虐行為の犠牲者である限りは、決して満足す ることはできない。われわれは、旅に疲れた重い体を、道路沿いのモーテルや町のホテルで休めることを許されない限り、決して満足することはできない。われ われは、黒人の基本的な移動の範囲が、小さなゲットーから大きなゲットーまでである限り、満足することはできない。われわれは、われわれの子どもたちが、 「白人専用」という標識によって、人格をはぎとられ尊厳を奪われている限り、決して満足することはできない。ミシシッピ州の黒人が投票できず、ニューヨー ク州の黒人が投票に値する対象はないと考えている限り、われわれは決して満足することはできない。そうだ、決して、われわれは満足することはできないの だ。そして、正義が河水のように流れ下り、公正が力強い急流となって流れ落ちるまで、われわれは決して満足することはないだろう。

私は、今日ここに、多大な試練と苦難を乗り越えてきた人々が、あなたがたの中にいることを知らないわけではない。刑務所の狭い監房から出てきたばか りの人たちも、あなたがたの中にいる。自由を追求したために、迫害の嵐に打たれ、警察の暴力の旋風に圧倒された場所から、ここへ来た人たちもいる。あなた がたは常軌を逸した苦しみの経験を重ねた勇士である。これからも、不当な苦しみは救済されるという信念を持って活動を続けようではないか。

ミシシッピ州へ帰っていこう、

アラバマ州へ帰っていこう、

サウスカロライナ州へ帰っていこう、

ジョージア州へ帰っていこう、

ルイジアナ州へ帰ってい こう、

そして北部の都市のスラム街やゲットーへ帰っていこう。

きっとこの状況は変えることができるし、変わるだろうということを信じて。

絶望の谷間でもがくことをやめよう。友よ、今日私は皆さんに言っておきたい。われわれは今日も明日も困難に直面するが、それでも私には夢がある。それは、アメリカの夢に深く根ざした夢である。

私には夢がある。それは、いつの日か、この国が立ち上がり、「すべての人間は平等に作られているということは、自明の真実であると考える」というこの国の信条を、真の意味で実現させるという夢である。

私には夢がある。それは、いつの日か、ジョージア州の赤土の丘で、かつての奴隷の息子たちとかつての奴隷所有者の息子たちが、兄弟として同じテーブルにつくという夢である。

私には夢がある。それは、いつの日か、不正と抑圧の炎熱で焼けつかんばかりのミシシッピ州でさえ、自由と正義のオアシスに変身するという夢である。

私には夢がある。それは、いつの日か、私の4人の幼い子どもたちが、肌の色によってではなく、人格そのものによって評価される国に住むという夢である。

今日、私には夢がある。

私には夢がある。それは、邪悪な人種差別主義者たちのいる、州権優位や連邦法実施拒否を主張する州知事のいるアラバマ州でさえも、いつの日か、そのアラバマでさえ、黒人の少年少女が白人の少年少女と兄弟姉妹として手をつなげるようになるという夢である。

今日、私には夢がある。

私には夢がある。それは、いつの日か、あらゆる谷が高められ、あらゆる丘と山は低められ、でこぼこした所は平らにならされ、曲がった道がまっすぐにされ、そして神の栄光が啓示され、生きとし生けるものがその栄光を共に見ることになるという夢である。

これがわれわれの希望である。この信念を抱いて、私は南部へ戻って行く。この信念があれば、われわれは、絶望の山から希望の石を切り出すことができ るだろう。この信念があれば、われわれは、この国の騒然たる不協和音を、兄弟愛の美しい交響曲に変えることができるだろう。この信念があれば、われわれ は、いつの日か自由になると信じて、共に働き、共に祈り、共に闘い、共に牢獄に入り、共に自由のために立ち上がることができるだろう。

まさにその日にこそ、すべての神の子たちが、新しい意味を込めて、こう歌うことができるだろう。「わが国、それはそなたのもの。うるわしき自由の地 よ。そなたのために、私は歌う。わが父祖たちの逝きし大地よ。巡礼者の誇れる大地よ。あらゆる山々から、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。」

そして、米国が偉大な国家たらんとするならば、この歌が現実とならなければならない。

だからこそ、ニューハンプシャーの美しい丘の上から自由の鐘を 鳴り響かせよう。

ニューヨークの雄大な山々から、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

ペンシルベニアのアレゲーニー山脈の高みから、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

コロラドの雪に覆われたロッキー山脈から、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

カリフォルニアのなだらかで美しい山々から、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

だが、それだけではない。ジョージアのストーン・マウンテンからも、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

テネシーのルックアウト・マウンテンからも、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

ミシシッピのあらゆる丘と塚から、自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。そしてあらゆる山々から自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。

自由の鐘を鳴り響かせよう。これが実現する時、そして自由の鐘を鳴り響かせる時、すべての村やすべての集落、あらゆる州とあらゆる町から自由の鐘を 鳴り響かせる時、われわれは神の子すべてが、黒人も白人も、ユダヤ教徒もユダヤ教徒以外も、プロテスタントもカトリック教徒も、共に手をとり合って、なつ かしい黒人霊歌を歌うことのできる日の到来を早めることができるだろう。「ついに自由になった!ついに自由になった!全能の神に感謝する。われわれはつい に自由になったのだ!」

Martin Luther King’s ”I Have a Dream” Speech

(アメリカ国務省 アメリカンセンタージャパンより引用)

August 28, 1963

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free.

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.

One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.

One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead.

We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by a sign stating: “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest — quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends – so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of “interposition” and “nullification” — one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

“My country ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!”

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

“Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”